Shepherding Model From Human Behavior

This project is focused on machine learning and aims to build a shepherding model based on human behavior. A simulation and data collection environment was built using pygame. Data was collected before being put into the training and evaluation pipeline. This project implements an Action Diffusion machine learning model.

GitHub: Shepherd Game

GitHub: Diffusion Policy

Video Demo

Shepherding and Diffusion Policy

Robotic shepherding involves using robots to guide a group of animals, such as livestock, towards a designated target. The challenge lies in coordinating multiple animals in a dynamic environment, where each animal’s behavior can be unpredictable. While a traditional algorithmic approach can work, it can struggle with unpredictable behavior and random starting environments. However, for shepherding dogs (and humans, to some extent), this problem is easily solved with intuition.

This is where diffusion policy comes into play. By sampling a distribution of human data, diffusion policy can generate actions and behaviors based off of human intuition. By manually herding sheep from different initial conditions, we can build a generalized shepherding model that mimics human intuition to successfully herd the sheep.

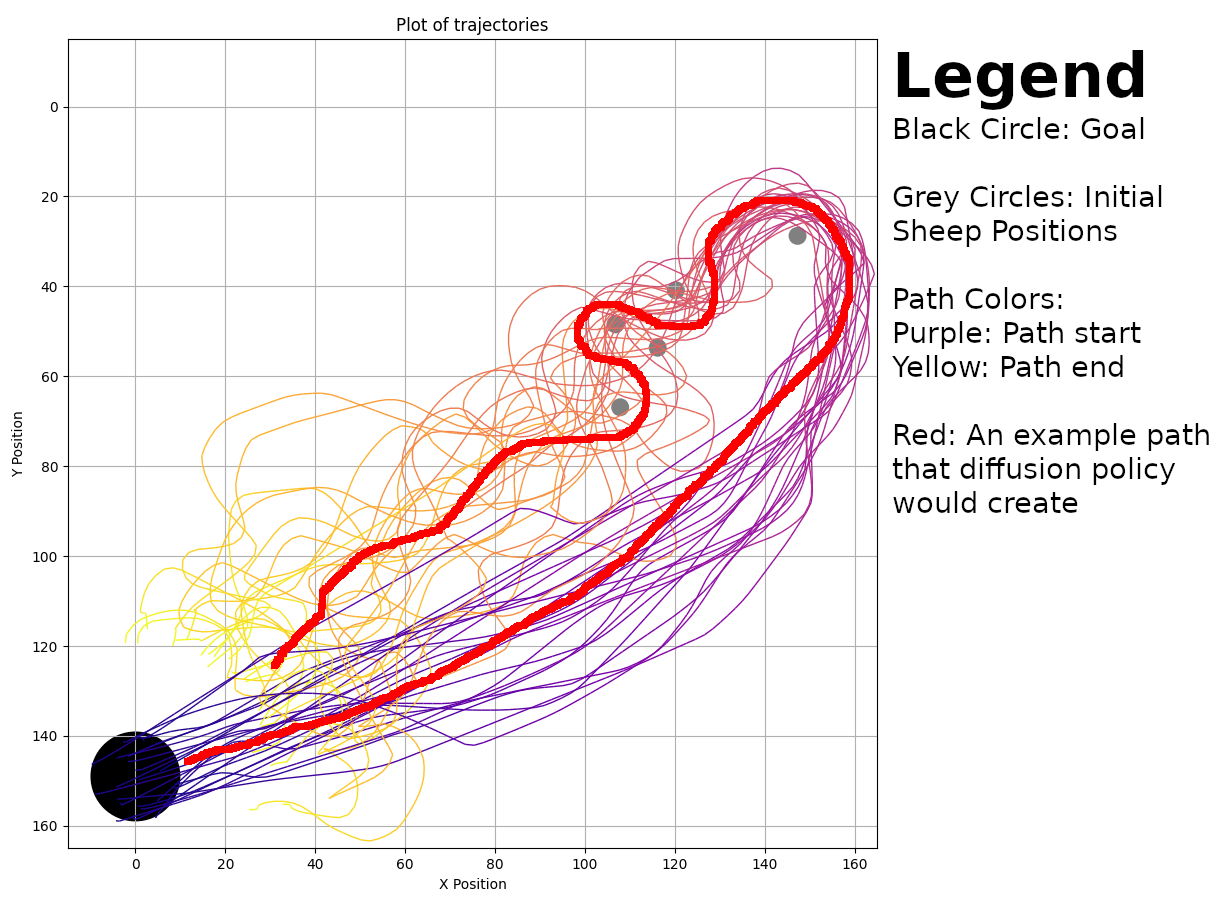

This picture displays 24 shepherding trials. Each trial has the same initial goal and sheep positions, with slightly varying shepherd positions. A diffusion policy model trained on this image would attempt to herd the sheep by following the red path. However, the model would fail to herd sheep with different initial positions, since there is no data for that. To create a generalized model, I would also need to use data with varying initial sheep positions.

Pygame Simulation

In order to collect data to train the model, and to evaluate the model, I needed a simulation environment. I decided to use PyGame since it satisfies following requirements:

- Easy to modify

- Allows user input (keyboard or controller)

- Can save the data (Using CSV files and images)

- Has easily tunable parameters

- Can display the game state visually

I used the Strombom Model to control the sheep. Most of the parameters are the same as the ones described in the paper, but I changed some to make herding easier. The resulting pygame window is shown below. The game uses extremely simply graphics, with each object represented by a circle. The sheep and shepherd have their headings represented by a triangle.

The state at each instance of the game is saved. The image is saved as a .bmp file while the positions are saved in a csv, in the following format:

data # Contains data for each game run

└── 1

└── img # Contains the image at each frame, as a bmp

└── 0.bmp

└── 1.bmp

└── ...

└── pos.csv # Contains the shepherd positions per frame

└── sheep_pos.csv # Contains the sheep positions per frame

└── target_pos.csv # Contains the target position

└── 2

└── ...

Inputs and Observations

Part of the project was figuring out what inputs and observations are a good choice. From the pygame simulation, positions and images are directly obtainable. Other variables can also be calculated, such as center of mass of the sheep or distance to the goal.

Using images as an observation also makes the model significantly worse. The GIF below shows 8 evaluations - the top row is a model trained with images, and the bottom row is a model trained without images. Apart from image data, both models were trained on the same set of data, with the same amount of information. The light blue path is the path that the shepherd has taken so far.

This behavior makes sense - the image is extremely noisy from a computer vision perspective, since the image data just has a single pixel changing and moving. Diffusion Policy uses a CNN for training using image data, which is great for picking up patterns in images. However, the image data from the PyGame simulation only has a single pixel moving around - which isn’t enough for the model to learn from. As a result, the image model failed to herd the sheep to the goal in most evaluations.

Adding other information, especially information dependent on other variables, also seemed to negatively affect the model performance. This is because this data doesn’t provide any new information, and acts as noise during the training process. The best model obtained was trained using just the positions of the sheep and shepherd.

Training Analysis

I anaylized the trained models using training graphs from wandb and an evaluation tool that I built. The wandb graphs contained useful training metrics and allowed me to compare models:

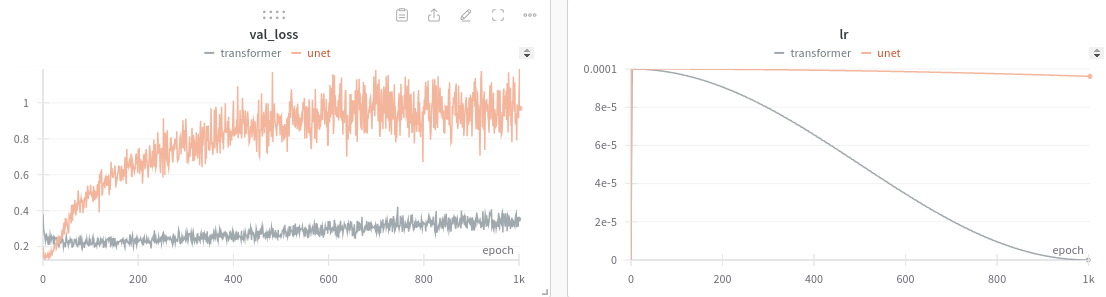

These graphs compare 2 models that I trained - one with a CNN architecture (the image model from above) and the other with a transformer architecture (the lowdim non-image model from above). From the graphs, we can see that the transformer model has a relatively constant validation loss and a decreasing learning rate, while the unet (CNN architecture) had an increasing validation loss and a relatively constant learning rate. These two metrics hint that the transformer model has converged on a good solution and the model isn’t improving as much. However, the unet model might be overfit or is learning from noisy data. These graphs are another indicator that training using image data is not a good choice.

The evaluation tool I built does the following:

- Take in a

yamlconfiguration file - Evaulate the model as desbribed by the configuration file

- What model to use

- What parameters to use for the simulation environment

- How many times to run each model

- etc

- Temporarily save the evaluation

- Repeat steps 2-3 for each run specified in the config file

- Sitch all of the evaluations together for a side-by-side comparison

- Use OpenCV and draw the path that the shepherds take

This is a comparison of a human and the model herding 100 sheep.

Herding Varying Amounts of Sheep

The model was trained on 5 sheep, so it expects observations for 5 sheep. However, the model can still be scaled to work with more, or less, sheep. To get the model working with less sheep, we can pad the remaining observations by just repeating sheep positions

The model can also be scaled to work with more sheep. This is done by dynamically targeting the 5 sheep that are furthest from the goal. As the model pushes in the 5 furthest sheep, it will also group and push any closer sheep in it’s path.

Limitations and Future Work

One of the limitations of this model is that it doesn’t scale well to multiple shepherds. When two models are run at the same time, each on a different shepherd, the shepherds follow an extremely similar path. This is because both models have the same inputs and observations, and they both attempt to generate actions from the same datasets.

Future work can explore the possibility of using multiple models and shepherds. This might include:

- Using multiple datasets

- Using dynamic targeting so that each model targets different sheep

Another potential future goal is to use two shepherd, one controlled by a human and one controlled by a model. This is currently limited by Python’s multi-threading capabilities. The model and PyGame (display and controller inputs) both use multi-threading resources, which ends up crashing.

References

Diffusion Policy Paper

Strombom Model

Nick Morales Diffusion Policy repository

Thanks to Matt Elwin, Lin Liu, Abhishek Sankar, Ishani Narwankar, and Courtney Smith for guidance and collaboration in this project